Researchers have described listening as the “Cinderella” of the four skills in language education. They say that just like Cinderella in the famous tale, listening is neglected, taken for granted and overlooked by its step-sister, speaking, which is given greater importance in research and in classrooms. The issue has attracted more and more attention in recent years – very recently so in Italy, where it featured in the latest national exam for English language teachers.

So, is it true that listening is the Cinderella skill? And does it matter to our teaching? In this blog post, we’re going to discuss:

- Whether listening can be called the Cinderella skill

- Why this matters (or doesn’t)

- How listening pedagogy can be improved (tips and tools)

Is listening really a Cinderella then?

To answer this question, we can look at two key variables:

- how much listening has been studied by researchers

- how much attention we give it in our classrooms

1. Cinderella in research

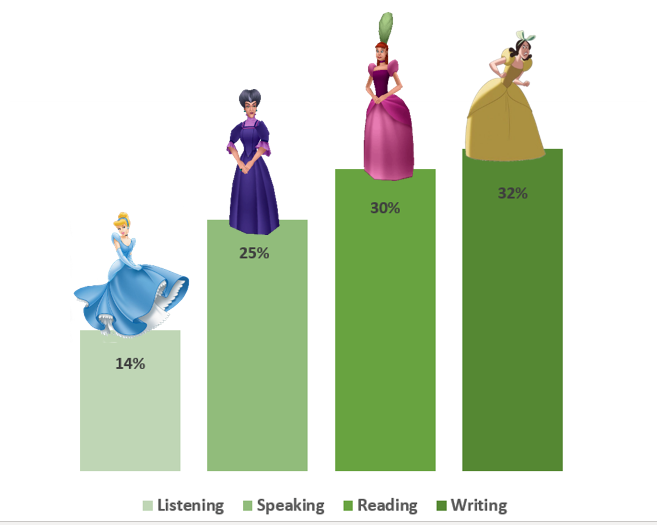

We’ve run the numbers to see how much the macro-skill of listening has been studied by researchers compared to reading, writing and speaking. Our analysis is based on 5 Google Scholar searches, looking up each skill together with the terms EFL, ESL, ELT, language teaching and language learning.

This is what we found:

Out of a total of about 7,500 articles we considered, only 14% were related to listening! 25% were about speaking, while both the written skills have received more than double as much attention as listening has – a little like Cinderella’s evil stepsisters did in the story (and yes, we’re deliberately keeping with the Cinderella analogy to delight you).

2. Cinderella in the classroom

But is research all that matters? We can see listening has been studied comparatively less, but we also know that coursebooks are chock-full of listening activities, that listening is generally not neglected at all in proficiency tests (look at Italy’s INVALSI, which only tests reading and listening) and ultimately, most of us teachers would probably say that we do listening in the classroom.

While we may do listening, however, the core issue that’s been discussed in the academic community is how we do it. The problem is twofold:

- We do listening for something else: recent research in Italian secondary schools conducted by one of #LanguagEd authors (Bruzzano 2020) suggests that more often than not, listening is done to learn vocabulary, grammar and as a prelude to speaking activities. Listening is not seen as an end in itself, i.e. developing all the listening processes and strategies that learners need to understand oral input;

- We test listening rather than teach it: a long-standing argument, put forward by listening scholars like John Field, claims that teachers follow a listen-check-answer pattern. They play a recording once or twice, learners answer comprehension questions, then check the right answers, and that’s it. This approach, it’s claimed, does nothing to develop the learners’ listening abilities for the future, but just continuously tests their existing abilities.

Does all of this matter?

Well, the fact that there’s gap between what research says and what teachers do in the classroom is old news, so much so that entire events are organised to address how to bridge this gap. Overall, however, knowing that less research is dedicated to listening (although this trend also has shifted in the last decade) also means that there’s less guidance in teacher training on how listening can be taught. In their research on teachers’ beliefs about listening, Suzanne Graham and her colleagues found that 82% said they had received no training on how to teach listening. Also, most teachers were unhappy with how they taught listening, but said they lacked the time and expertise to find alternatives.

The conception of listening as a means for something else (speaking, vocabulary, grammar) is widespread and it can indeed be a useful approach to enhance language acquisition, as confirmed by the research: just think about the benefits of watching TV series with captions on vocabulary acquisition.

Also, seeing listening as a means to something else and not as an end in itself can be contextually appropriate: in Italian schools, where CLIL is common, a lot of listening will occur through the teaching of subjects like Maths and Science – though there will hardly ever be an explicit focus on developing listening processes in it. It’s also true that critical thinking is increasingly regarded as an important soft skill to develop in school: listening is an ideal candidate in this sense, as teachers can choose among myriads of freely available videos (e.g. on global issues or current events) to use in activities focusing on critical thinking – so again, not explicitly on listening processes.

How could we improve the way we teach listening?

So keeping in mind that we always need to deal with what is contextually appropriate, we can probably accept one key message from the research and gradually integrate it in our teaching: listening can also be taught as a skill in its own right.

Based on this, here are some tips to teach rather than just test listening. You can integrate these tips with whatever your current approach may be:

1. Focus on the process, not just the product

Effective listening includes bottom-up processing (i.e. understanding sounds, syllables and words) and top-down processing (i.e. drawing upon one’s knowledge to interpret a text), as well as metacognition (the ability to plan, monitor and evaluate one’s listening). We explain bottom-up and top-down listening in 3 minutes in this video:

If we always just play a recording, students answer questions and then we correct those questions without any follow-up, we’re only focusing on the product of their listening (i.e. their answers), rather than the processes they employed to try to understand. Students who choose the same option in a multiple choice question may have arrived at their answer in very different ways (e.g. guessing versus looking for key words) and by understanding different portions of the text!

Therefore, we could concentrate on:

- Their listening mistakes: after you correct their answers, elicit their difficulties or ask them why they gave a certain answer. This will give you an insight into why they answered right or wrong. Especially with wrong answers, discuss with them why their answer was wrong: for example, if a student doesn’t hear the sound /t/ in “I wasn’t happy” and thinks the speaker was happy, you can replay the section and raise their awareness of the importance of contracted negations in English. You can also do a Diagnostic Dictogloss, as we explain in this blog post.

- Bottom-up processes: simple exercises like dictations, gap-fills or trying to transcribe small sections (i.e. 20 seconds) of a listening text will do wonders for developing the learners’ ability to distinguish sounds and words, as well as word boundaries.

2. Help learners develop metacognition

Metacognition is the ability to think about thinking. Applied to listening, it means planning, monitoring and evaluating one’s listening. Learners with better metacognition tend to be better at applying listening strategies and feel more in control of listening – especially since listening is often the one language skill they perceive as most uncontrollable.

Activities to enhance metacognition might include:

- making predictions about listening and – crucially – verifying them after listening

- discussing how to plan for different types of listening activities (e.g. planning will be different for taking notes during a lecture and for listening to a podcast for fun)

- after listening, reflecting on what strategies learners have applied that were successful and unsuccessful, and why

- keeping a simple but systematic record of learners’ difficulties and ways to tackle them (we explain how in this video)

- giving learners a framework to do listening activities at home

3. Integrate listening for other purposes and listening in its own right

As we said, thinking of listening as the gateway to other skills and systems can be a valid approach. You can also alternate this with an approach that develops the processes of listening for the sake of listening.

How, you ask?

One straightforward answer is: exploit the full potential of video. You don’t have to limit yourself to a video that shows a certain grammar structure or lexical set: you can also help learners develop their bottom-up and top-down processes! Here are some examples with freely available resources:

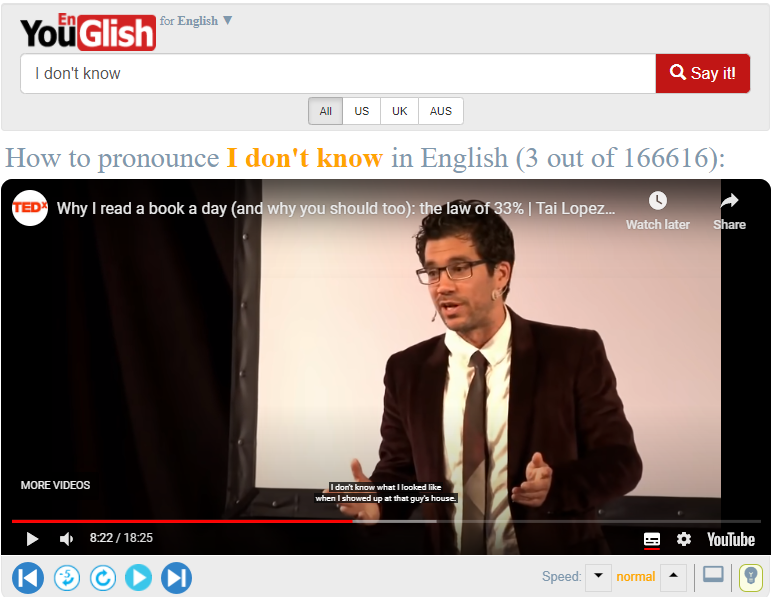

- Youglish: did your learners fail to recognise a word, a lexical chunk or an idiom in a listening activity? Are you focusing on specific words or grammar structures and want your learners to understand how they’re pronounced in real life? Look no further than YouGlish: with a simple search, we found more than 166,600 examples of just the phrase “I don’t know”!

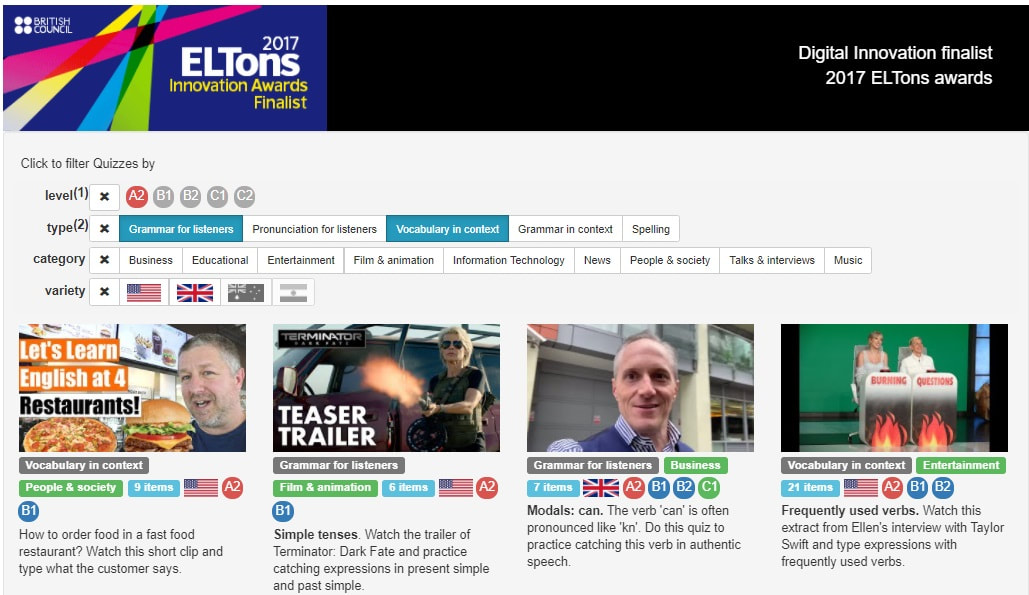

- Tubequizard: a British Council ELTon award finalist, collecting engaging authentic videos that integrate bottom-up practice of recognising sounds and words with a focus on vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation in context. Use their ready-made quizzes for different levels or make your own!

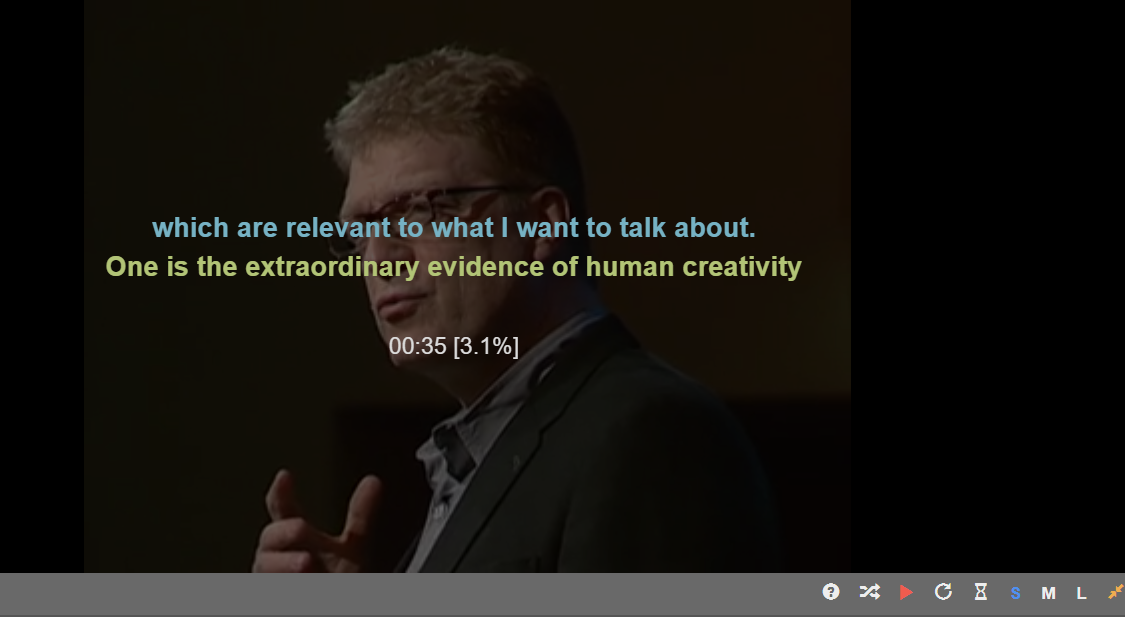

- TED Search Corpus: look for a TED or Youtube video you like and work on it through this website. You can search words or chunks, select key words and use the brilliant pause-and-check function: students can watch without subtitles, and whenever they don’t understand, they can pause and the subtitles from the last few seconds (followed by the translation in another language, if you want) will appear!

This way, they don’t get distracted by subtitles while they’re listening, but they can check their understanding whenever they need to. This also enhances their autonomy and metacognition (in the ability to monitor and evaluate how much they’re understanding).

Conclusion: listening as Cinderella – fairy tale or reality?

All in all, listening hasn’t been studied as much as the other skills and there seems to be less guidance for teachers as to how to teach it, although that has improved over the last few years with increased interest in this subject by researchers and authors. A common approach that has been observed (and critiqued) is one that tests the students’ production of correct answers to comprehension questions rather than help them learn how to listen.

These factors might lead us to conclude that yes, listening still seems like a Cinderella in research and teaching practice if we only look at listening only as “developing listening comprehension in its own right”. However, many teachers, especially school teachers, conceive of listening as useful for other purposes, and rightly so, since this may be context-appropriate and it can lead to improvements in language acquisition (e.g. vocabulary and pronunciation).

So in reality, whether listening is a Cinderella depends in no small part on what we mean by listening: it’s a bit of a Cinderella in research, but it does feature in classrooms – perhaps though, not in a way that explicitly focuses on developing listening processes. While teachers may do listening in different ways, one thing seems advisable: we can all learn to integrate with our current practices a focus on the bottom-up, top-down and metacognitive processes that are needed for successful listening comprehension. This is aided quite considerably by access to technology.

Do you want to find out more?

We discuss listening and how to teach it in details in Unit 15 of our Language Teaching Methodology course. We also discuss how to choose authentic materials featuring “native” and “non-native” speakers in Unit 5 of our Designing Activities and Lessons course.

So what are your favourite resources and activities for listening? Tell us in the comments!

References

Bruzzano, C. (2020). Why do you do what you do? Teacher and learner beliefs about listening in the EFL classroom. In: Mackay, J., Birello, M. and Xerri, D. (eds.) ELT Research in Action. Bringing together two communities of practice, Faversham: IATEFL. http://resig.weebly.com/uploads/2/6/3/6/26368747/eltria2019formattedfinal2.pdf

Graham, S., et al. (2014). “Teacher beliefs about listening in a foreign language.” Teaching and Teacher Education 40: 44-60.

Pingback: Designing and conducting an Authentic Listening course – Part 1 – PavilionELT